As a former NASA engineer who worked on ground processing for the International Space Station at Kennedy Space Center, I’ve had the rare privilege of seeing the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA) in action—and even supported missions that rode atop it. This article is both a close look at the new 10360 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft from the AFOL perspective and a deep dive on the real vehicles it honors from an aerospace perspective.

Bricks and Boosters

Space is big. The machines that make space travel possible also tend to be on the large side. Sure, the Mercury, Gemini, and Vostok capsules that first carried humans away from Earth were fairly small—but the rockets that launched them were not. And those rockets required equally massive infrastructure to move them around.

Large barges, ships, and railcars quickly played a role (and still do), but aircraft also became key players. NASA’s first aerial rocket mover was a heavily modified KC-97 Stratotanker, retrofitted into the Guppy in 1961. In 1965, the Super Guppy was introduced and supported the Gemini, Apollo, Skylab, and International Space Station programs. NASA still uses a version of it today: the Turbine Super Guppy developed by Airbus.

The Soviets, too, developed aircraft to move their shuttle, the Buran, most notably the AN-225 Mriya, the heaviest aircraft ever built and holder of the longest wingspan. Sadly, it was destroyed at the start of the ongoing war in Ukraine. Its final mission? Delivering COVID-19 tests from China to Billund, Denmark just three weeks before its destruction.

But perhaps the most well-known aircraft in this space-travel logistics story is NASA’s Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA), a modified Boeing 747 that ferried the Space Shuttle fleet across the country.

747 Queen of the Skies

Designed in the late 1960s and entering service on January 22, 1970, Boeing’s 747 is possibly one of the most easily recognized aircraft in the world. Its distinctive partial upper deck gives the aircraft its signature hump, and its four turbofan engines make a ‘47 easy to spot.

The 747 was created in response to a request from Pan Am Airlines for an aircraft 2.5 times larger than the Boeing 707 that could operate at 30% lower seat cost (a measure that factors in operating cost, seat availability, and range). The first “Jumbo Jet,” as the press dubbed it, was Boeing’s answer.

With a then-unique twin-aisle configuration—two aisles and three rows of seating in a 3-4-3 arrangement in coach—the 747 helped meet Pan Am’s coach requirements. Over time, the aircraft evolved through several configurations indicated by certain dash numbers: the -100 (original), -200, -300, -400, SP, and -8. Each offered variations in seating, range, and performance, allowing airlines to optimize their fleets for different route demands.

The 747 has played many other roles as well. According to the Internet Movie Plane Database, it appears in more than 1,000 TV shows and movies. (I didn’t dig through that entire list, but I’m sure plenty are appearances as Air Force One/VC-25—technically a call sign used when the U.S. President is aboard, but it’s become shorthand for the aircraft itself.)

There are currently two VC-25A aircraft (based on the 747-200) and two VC-25Bs in production. Other unique 747-based configurations include:

The Dreamlifter: A heavily modified 747 used to transport large 787 components from Boeing’s worldwide supplier base. I happened to catch one in flight once—just looked out a window at the right moment!

The YAL-1 Airborne Laser Demonstrator: An experimental antimissile laser test bec.

SOFIA (Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy): NASA and DLR (Germany’s space agency) installed a massive infrared telescope into the back of a 747SP. I got to hear a NASA pilot talk about flying it—supporting the telescope, adding a sliding fuselage door, and still keeping the aircraft stable in flight was no small feat.

And finally, the two Shuttle Carrier Aircraft: a 747-123 and a 747SP, both modified by NASA to ferry the Space Shuttle.

Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA)

I could go deep into the development of the Space Shuttle to explain why the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA) was needed, but I’ll stick to the short version here.

(If you want a deep dive, I highly recommend Ron Miller’s The Dream Machines, and Dennis Jenkins’ Space Shuttle: The History of the National Space Transportation System – The First 100 Missions as well as his incredible three-volume set Space Shuttle: Developing an Icon 1972–2013. I paid way more for the first two when I got them new, and wow—the Jenkins set is way more expensive now! They’re incredibly thorough, and to be honest, I haven’t read them all myself.)

Now that you’ve checked your local library for those...

The SCA was necessary because the Shuttle design didn’t include room for air-breathing jet engines, and attaching removable engines was deemed more complicated than necessary. That left NASA with a big problem: how do you flight test a giant glider and transport a spaceship cross-country from California to Florida? Shipping it by boat through the Panama Canal would have been slow, but more importantly, the glide tests were absolutely critical to proving out the Shuttle program.

So NASA studied aircraft big enough to do the job. The top two contenders were the Lockheed C-5 Galaxy, operated by the U.S. Air Force, and Boeing’s 747. The Air Force (which co-funded the Shuttle program and whose requirements influenced the Shuttle’s delta wing shape and the original California launch site) said, “You can use the C-5, but we keep priority.” Understandably, NASA decided it would be really nice to have its own aircraft.

NASA procured a 747-100 from American Airlines and worked with Boeing to modify it into the first Shuttle Carrier Aircraft. That aircraft became N905NA.

Hey I even got the moon in this picture!

Modifications included structural reinforcements for the three Shuttle attachment points (which aligned with where the Shuttle attached to the external tank), reinforcements to the horizontal stabilizer, and the addition of endplates to improve yaw stability (that’s your left-right turning). Most of the interior was removed, more powerful engines were added, and a variety of temporary systems were installed for the Approach and Landing Tests (ALT) with the Shuttle, Enterprise. That’s how the 747 in LEGO set 10360 came to be.

Later, a second Shuttle Carrier Aircraft was acquired—partly as a result of the Rogers Commission (which investigated the Challenger accident) and partly because weather issues at Kennedy Space Center in Florida meant Shuttles were still frequently landing at Edwards Air Force Base in California. So in 1990, NASA took a 747-SR (Short Range) being retired by Japan Airlines (JAL), modified it, and designated it N911NA.

Both SCAs remained in service until the end of the Shuttle program. Today, N905NA is on display at Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, with a mock-up Shuttle Independence mounted on top. N911NA is on display at Joe Davies Heritage Air Park in Palmdale, California.

Photo by Robert Pearlman of CollectSpace.com, showing SCA Orbiter Mount referenced in instructions Manual

Seeing the SCA

Atlantis on SCA Tail Number N905NA after STS-117

Early in my career, I had the opportunity to work at Kennedy Space Center (KSC). I was an engineer on the ground processing team for the International Space Station, where we prepared ISS modules for flight. That means—yes—some of the hardware I touched (through gloved hands, of course, because even the oils from your skin can cause problems in space) is currently in orbit!

Endeavor on SCA Tail Number N911NA after STS-126

While I was at KSC, three Shuttle missions landed at Edwards Air Force Base instead of Florida due to weather, and all three needed to be ferried back to KSC aboard the SCAs. I was fortunate enough to see two of those return flights: Atlantis on N905NA after STS-117, and Endeavour on N911NA after STS-126—both missions where I had helped process hardware for flight. I missed the return of Atlantis on N911NA after STS-125, the final Hubble servicing mission. I probably had a job scheduled to run and couldn’t get away to step outside and watch it land.

Like any landing, seeing the SCA marked the end of a mission—the Shuttle was home, and the next round of work could begin to get her ready for the next flight. There was always a sense of joy and excitement in those moments. Shuttle landings are incredibly fast, and unless you’re right at the Shuttle Landing Facility, you mostly just hear the double sonic booms as it comes in—but you rarely see the Orbiter itself.

Endeavor on SCA Tail Number N911NA after STS-126

The SCA return flights were different. They would do a couple of low-level flyovers of the Space Center before landing, giving everyone a chance to come outside and watch. It felt like a unique airshow—an incredible visual payoff and a real celebration of the mission. Launch and landing days always had a special energy. They were visible reminders of how much effort the ground crews put into making spaceflight happen.

A Shuttle in Paris

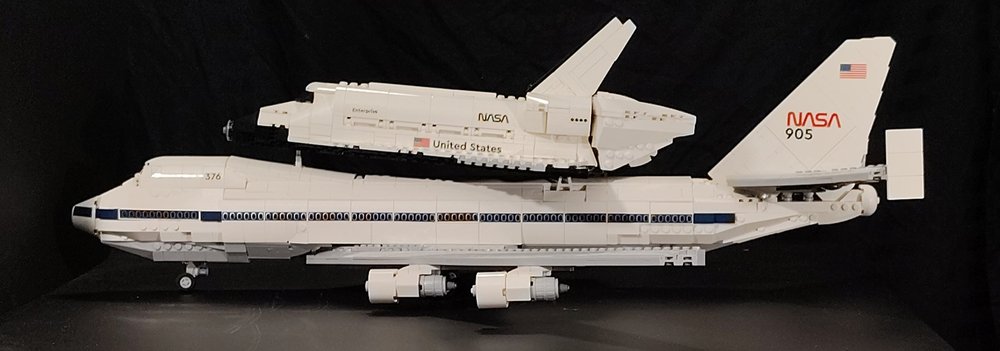

While I was lucky enough to see the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft in person during its working years, this LEGO set captures a different—but equally memorable—moment in its history. 10360 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft features a very distinctive look for the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft and Space Shuttle Enterprise. It captures the configuration used when the pair visited the Paris Air Show in 1983.

When I first saw rumors of this set, I had two big hopes. First, that it would feature the American Airlines livery (because we would get lots of shiny silver parts!). And second, that it would include a Shuttle other than Discovery. I was especially hoping for Enterprise so the set could represent the Approach and Landing Test (ALT) configuration. Later rumors named the set Space Shuttle Discovery and the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, which got me spun up about LEGO only ever making models of Discovery (though I later discovered that set 7467 has a tiny version of Endeavour.) But at least one of my wishes came true: we got Enterprise.

Family Photo from Left to Right: Discovery (7470), Endeavour (7467), Enterprise (10360), and Discovery (10283) again. Hopefully someday we will have official sets of Columbia, CHALLENGER, and Atlantis too!

In a roundtable discussion with other fan media, LEGO designer Anderson “Andy” Ward Grubb explained that the design team wanted to capture a more worldly moment in Shuttle history. The Paris Air Show visit was part of a larger European tour, and the “376” marker was specific to that tour—it served as an identifier for the airshow.

Image via Our PLanet

I suspect that the trip likely served a dual purpose. Besides being a public showcase, it probably helped validate that the Shuttle and SCA could safely make a transatlantic crossing. This was important because several overseas bases were designated Transatlantic Abort Landing (TAL) sites in case a Shuttle ever had to make an emergency landing shortly after launch. Sites in Zaragoza and Morón, Spain, Istres, France, and RAF Fairford, England were prepared for this scenario by the end of the Shuttle program. If you’ve ever listened closely to the launch audio, you might recognize those names.

Extended Family!

Thoughts on the Set

Talking about LEGO now, the assembled set looks really good! It’s large and well-designed, and there’s a lot of fantastic engineering packed into it. That said, the aerospace nerd who shares headspace with my BrickNerd brain does have a few things to point out from the negative column.

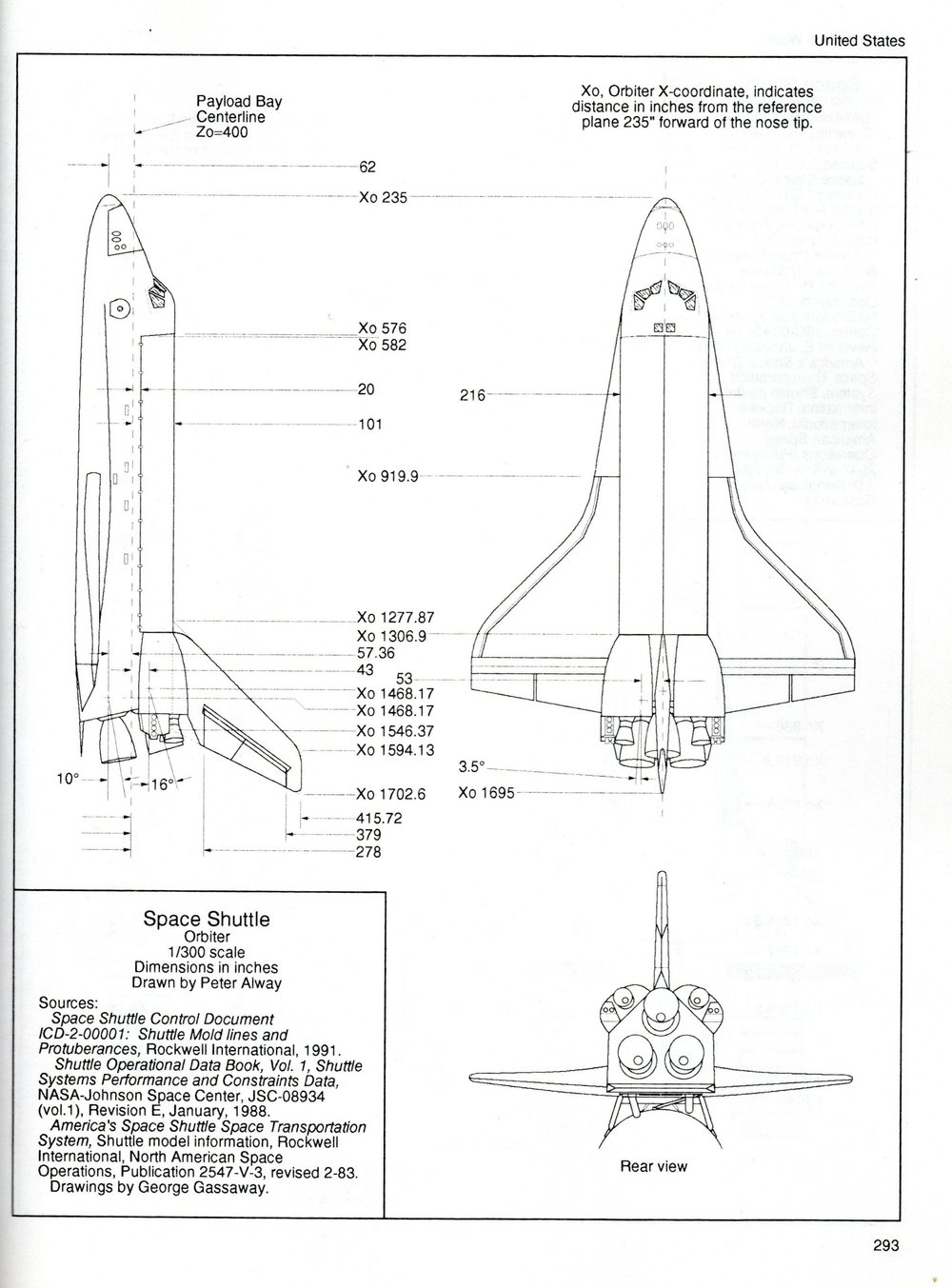

Rockets of the World 4th Ed P. Alway. Notice how the OMS Pods are set at an angle on the aft fuselage and how they stick out.

First up: the Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) pods on Enterprise are too big and too square-ish, especially noticeable from the front. From the side, they’re not so bad. I brought this up in the roundtable discussion and learned that there were three main design constraints behind this choice:

The OMS pods were the most likely structural location for users to press when snapping the Shuttle onto the SCA, so they needed to be sturdy.

The removable tail cone needed to be swappable with he engines to make everything fit. A hollow cone surrounding the engines like the real one just isn’t feasible at this scale.

The best shaping of the tail cone looked better with the larger OMS pods.

Yes, other sets have done better OMS shaping even at a similar scale (see 31117), but considering the unique structural and aesthetic needs, this isn’t a deal-breaker for me.

See how large the OMS pods are?

Top View of Large OMS pods

31117 is a similar scale and much better

Top Comparison

The Creator set is likely one of the better OMS Pods designs at this scale

The area around Enterprise’s cockpit windows also looks a little odd, though it’s only really noticeable up close. On the SCA, I would have loved to see doors on the landing gear, but I can understand why they were omitted.

One thing that really stands out in the box art is the 6x6 tile with the NASA logo on the vertical stabilizer. Between the lighting and the sticker reflection, it looks like the tile sticks out a ton. In real life, it’s not as bad—maybe a quarter plate bump. If it really bugs you, you can “fix” it using six of the older headlight plates with the thinner rings. Just be warned, Richard from Rambling Brick pointed out that the old white plastic won’t look as white, so any color mismatch or yellowing may still bother you.

Final nitpick: the instructions claim the wings have a 45-degree sweep angle, which is true for the LEGO model. But on the real 747, the wing sweep is actually 37.5 degrees—a much harder angle to capture in LEGO form. So not technically accurate, but forgivable.

I didn’t take any build photos—life was busy, the lighting wasn’t great, and honestly, I didn’t want to spoil the fun for you. But I’ll give two warnings:

Steps 282–292, where you build the rear attach points for the Shuttle, are very fiddly. I exploded that section at least three times—pieces went everywhere. Go slow and gentle. Once built, it’s super sturdy.

Bags 13 and 14 (the SCA wings) require a lot of attention. It’s really easy to be one stud off and not realize it until several steps later. It was late and I was distracted, so I definitely made errors—but if you stay focused, you’ll be fine.

Engineering Highlights

In the roundtable, we talked a lot about the landing gear, and it really deserves a spotlight. The SCA build feels almost like a Technic set for several bags—you build a fully functional mechanical core, then wrap a System-based skin around it. It’s a fascinating design choice, and I really enjoyed watching the mechanism come together. I also appreciated learning that it took about 20 design iterations to get it right.

The landing gear assembly is essentially an evolution of what was done on the Concorde (set 10318), but several other design paths were explored along the way. One particularly exciting element is the brand-new 4-wheel landing gear truck piece. This opens up some neat possibilities for future sets, and I hope it gets used frequently. It’s more Technic than System, which affects spacing a bit—which is also why it’s used in the nose gear rather than the standard System nose gear piece.

This set is also an evolution of design work that began with Mike Psiaki’s Saturn V (sets 21309 / 92176). When he was experimenting with new ways to create round shapes, it led to the original sketch model for the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft and set the scale from the start. That scale is roughly 1:115, which pairs nicely with the Saturn V’s 1:110—so they should complement each other well.

The livery is captured well using a mix of prints and stickers. Most of the stickers are on the larger side, but I had no issues getting them aligned to my standards.

Despite the nitpicks I mentioned in the previous section, the wing construction is really something to admire. They not only replicate the approximate sweep of the 747’s wings but also include a visible dihedral (the upward angle of the wings from the fuselage). And they’re solid—no noticeable droop. Andy specifically stressed in the roundtable that they worked hard to make sure the wings stayed straight, and it shows.

Even more impressive? Despite weighing in at 3.83 lbs (1.74 kg) combined, the SCA and Enterprise are totally swooshable! You can lift both at the same time by the Shuttle alone, but I don’t recommend it—I can get about three inches off the table before the SCA drops off. Definitely not a swooshing technique I’d trust.

And one last fun fact for the SHIP (Seriously Huge Investment in Parts) fans out there: if you put the Enterprise and SCA and measure nose to tail, this combined model exceeds 100 studs. So while the SCA itself clocks in at only 76.6% of a SHIP, the full combined model breaks the barrier, so I’m officially calling it an Honorary SHIP.

If you’re a fan of the U.S. Space Program, you’re probably already at the “shut up and take my money” stage. If you’re an aviation nerd, this is an excellent model of an iconic aircraft at an impressive scale—24.125 inches long and 21 inches wide. And if the NASA livery isn’t your thing, it won’t take much to remove the Shuttle mounting pieces and tweak the exterior to your liking (depending on your comfort level with custom stickers, water-slide decals, etc.).

Oh—and if you love 2x2 and 2x4 bow pieces, this is your parts pack. You’ll get a ton of them in white and light bluish gray!

Sticking the Landing

Since this is part of the LEGO Icons line, a lot of people are going to call this set “iconic.” Normally, I think that word is overused—it’s become the go-to description for anything remotely cool or recognizable. But in this case? I really can’t argue with it.

The Boeing 747 has been a symbol of commercial aviation for over half a century. While its cultural dominance may be fading as newer long-range aircraft become more prominent, the 747 will always invoke the golden age of air travel and the rise of international connectivity. Likewise, the Space Shuttle remains instantly recognizable to people around the world. Its silhouette, launch stack, and mission legacy have become shorthand for human spaceflight.

So while I have my nitpicks, this model does an impressive job of capturing both of these masterpieces of aerospace engineering at a meaningful scale. It’s a rare LEGO set that manages to balance technical accuracy, historical storytelling, and building fun all in one box. Whether you’re drawn in by the Shuttle’s legacy, the 747’s legendary status, or just the satisfaction of watching a beautifully engineered landing gear system click into place, you are going to enjoy this set.

For fans of space, aviation, or just LEGO, 10360 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft is a build that truly sticks the landing.

LEGO Icons 10360 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft will be available beginning May 15th for US $230 | EU €230 | CA $300 | UK £200 | AU $350.

DISCLAIMER: This set was provided to BrickNerd by LEGO. Any opinions expressed in this article are those of the author.

What is your favorite space shuttle? Let us know in the comments below!

Do you want to help BrickNerd continue publishing articles like this one? Become a top patron like Marc & Liz Puleo, Paige Mueller, Rob Klingberg from Brickstuff, John & Joshua Hanlon from Beyond the Brick, Megan Lum, Andy Price, Lukas Kurth from StoneWars, Wayne Tyler, Dan Church, and Roxanne Baxter to show your support, get early access, exclusive swag and more.